I find that it sometimes takes a while for new users to get used to Gingko.

I always say there’s no “right” way to use Gingko. But there is one point that might help you see your trees differently. And it might make the difference between getting stuck on an idea, and having it just flow onto the page.

First of all, think about the phrase “flow onto the page”. It implies that there is a stream of information that begins in your mind, and needs to pass through a very narrow channel (your typing fingers), to emerge on a Gingko tree.

Thinking of writing as information flow brings in a few analogies from the field of communication theory, which I find helps explain why a Gingko tree is not just an outline.

When arranging and organizing a tree, you shouldn’t be thinking in terms of categories (“Where should this go?”), but in terms of lossy compression and a sum of parts.

Lossy Compression

If you’re old enough, you might remember that back in the ancient World Wide Web (or Information Superhighway), you would sometimes watch an image download painfully slowly.

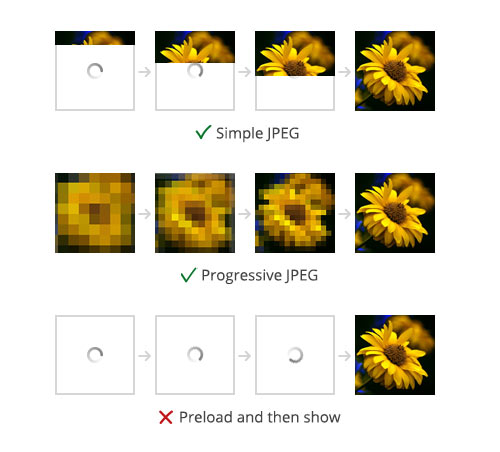

Some images would come in line-by-line, but others would seem to come in first in a blurry form, and then get gradually more refined.

The latter kind use what’s called “Progressive” JPG compression. And the idea is simple. Instead of transmitting one pixel at a time, at full resolution, you send a very low resolution version[1], and then send more information to sharpen it up in stages.

This has a number of benefits.

First, you get to see the whole image much sooner. And since the brain is so good at pattern matching, often the extremely blurry first few bits of an image are all that’s needed to understand what you’re looking at.

Secondly, by doing it this way, if for some reason the connection is lost a third of the way through, you don’t end up with the top third of a landscape (nothing but blue sky), and no information at all about what the rest of the image contains.

JPG in general is called a “lossy” compression format, because when saving an image as a JPG, a lot of the information is actually thrown away. The format is clever enough to throw away only stuff that most people wouldn’t notice anyway (subtle changes in color over a large space, say). The format is also “progressive” because it sends the data for the complete image at very high loss rate, and then progressively sends more information.

Ok, so enough about images. What does this tell us about writing?

Write Progressively

If you’re writing in Gingko and are in flow, by all means, do whatever works for you. But if you’re writing and you find yourself stuck, try to see your whole tree as being like those progressive images.

Level one, at the far left, should contain one or just a few cards[2]. And the important point is, this card should be a complete but blurry summary of the whole document.

All levels in from that are just progressive enhancements of the original top-level summary.

Sum of Parts vs. Planned Categories

In practice, the biggest difference between the “progressive enhancement” approach, and the outlining/categorization approach, is that your tree shouldn’t contain any title-only cards.

It’s a subtle difference, but I believe it does two things.

- It moves your mind from a very abstract realm (“categories” and “folders” and “headings”), into a very concrete realm (“What is the whole about?” “How can I cut it up?”).

- Categorization is often pre-emptive and stifling, because you are thinking about the “best way to organize” a tree, rather than simply breaking apart an idea into its component parts, and breaking those components still further.

- With categorization, you often end up with more or fewer categories than you need, and you often jump too quickly to a high level of detail.

A whole story can be told in a few sentences, or over a span of 70,000 words. But the only way to get from one to the other is in various stages of progressive enhancement.

Transfer Benefits

The benefits of progressive downloading of an image to your browser are the same as those that come from the progressive “downloading” of an idea into Gingko.

- You can see patterns more easily.

- If you stop, it’s easier to pick up again because you have a more complete picture.

- You’re taking one idea and breaking it up in stages, rather than taking a hundred ideas and trying to organize them all at once.

Theory & Practice

There are probably as many ways of using Gingko as there are Gingko users, so this is not “the way it should be”, but just another idea to keep in mind if you get stuck.

Rule of thumb, if you find yourself thinking “Where should this card go?” often, then try going to the root and summarizing the whole document. What’s the big picture? How does that break up into smaller ideas? And actually write those summaries. This should help you see the natural patterns in your work.

As always, would love to hear your thoughts.

[1] It’s not actually sending a low-res version, but rather the “most important bits” according to a series of algorithms.

[2] This only applies for trees that are to be seen as documents, not as processes. That is, it doesn’t apply for trees that are for organization, GTD, or project planning.