It’s spring, and my wife and I have been decluttering our apartment. We do this more often than most, and get more ruthless each time, but there’s one thing that I keep hanging on to: assignments and term papers from my Physics undergrad program.

I’ve been trying to figure out why I can’t just get rid of them, like we did with so much of our old clothes.

After all, they don’t mean anything to anybody besides me, and I keep them stuffed in a trunk, and never see or show them to anyone unless it’s to decide “should I throw this away?”

But I know showing off runs counter to my nature*, so I shouldn’t be surprised they’re not showcased. Also, who frames their assignments?

*(which can cause problems, since I’m currently the one in charge of Gingko’s marketing…)

What is surprising is that I feel the quality of that work is sometimes far better than some of the work I’ve been putting out there recently with Gingko and other projects that are far more important than some Quantum Field Theory assignment.

For quite a while I assumed the answer was “lack of time”. I’m the founder of a startup and father of a one year old boy, sharing all childcare and household duties* with my wife (who also runs a vegan skincare business). I don’t have a lot of uninterrupted time.

*I believe equally, but I should note my wife disagrees.

But two weeks ago, my wife went with our son to go visit his grandmother for 5 days. The apartment was eerily quiet, and I had all the time in the world.

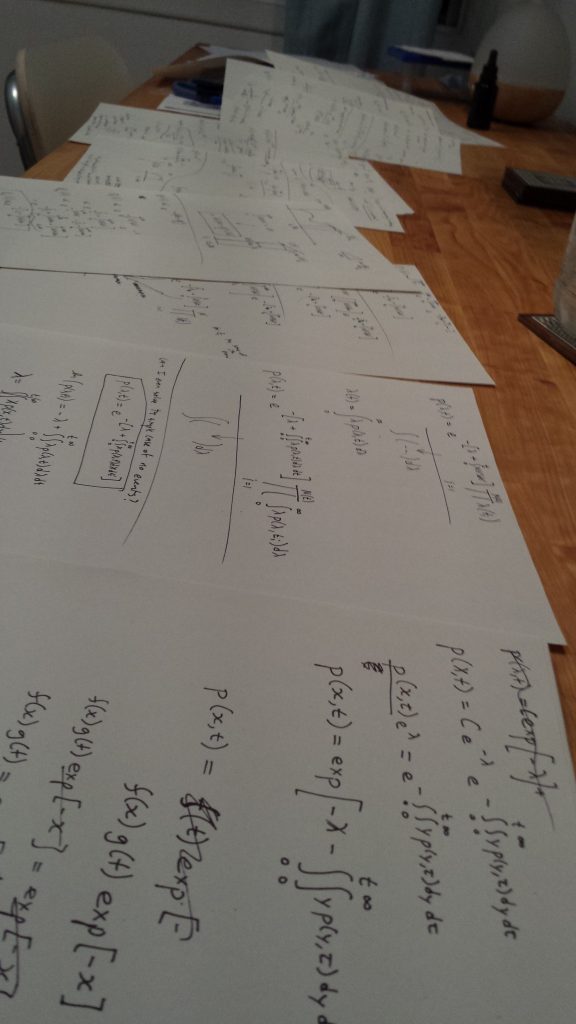

Now was my chance to produce something that I would be proud of, but nothing came of it. I did find an interesting problem to work on, and went on a sort of “math binge” to tackle it. But the end product was just a bunch of scattered notes.

So, time is not the main issue.

But in looking over these assignments, I was once again reminded of a simple truth via an exceptionally indirect path:

The truth is that constraints lead to simpler solutions. And the reminder comes from Quantum Mechanics.

Quantum Mechanics, in a few words, is how we study the motion of particles at very small scales, where everything is blurry (including the particle itself). And not blurry as in “we can’t see it” but blurry as in, “it has no definite position”; the particle itself is literally spread across space in a weird kind of cloud.

Some of the types of questions you can answer with QM is, “if you throw this particle at a wall that’s this thick and this high, what’s the probability that it’ll just suddenly appear on the other side?”.

And no, the answer is not “zero”, which is what makes QM weird.

To figure stuff like this out, in the simplest of cases, requires solving Schrodinger’s equation:

![]()

One of the first exercises in an introductory QM course is to answer “Ok, so you have this one particle constrained to be within this box. What are the ways it can move?”

And here’s the thing:

- If the constraining walls are infinite and truly impenetrable constraints, the solution you find is extremely simple: just a bunch of sine waves.

- If the walls are anything less than infinite, the solution isn’t just hard, it becomes absolutely impossible to find exactly.

The reason is that, with only weak constraints, the particle “leaks” out into the world, and though it’s “most likely” in the box, there is some very small chance it could be a long ways outside of it.

And though these chances are small, we are forced to include the entirety of space in our calculations.

A Generative Analogy

I am sure you’ve heard that “constraints lead to creativity”. I have heard this as well, and said it myself several times.

But nothing brings an idea home as much as the combination of a learning experience combined with a deep generative analogy that resonates with me.

And while it might seem silly that I’m evoking Quantum Mechanics to explain common sense (clearly an odd situation), to me it provides a model for this idea in a way that allows me to understand why constraints lead to creativity. And why it only works if the constraints are truly rigid.

Without rigid constraints to your problem, the possible solution “leaks” out into the entirety of space, meaning that you’re forced to imagine the entire solution space, no matter how unlikely those outcomes are.

Next time I’m working on a project, besides the usual steps of identifying a clear purpose, and envisioning a clear outcome, I need to make sure to expressly state the impenetrable constraints of the project.

With that said, my 90 minute timer for this post is running out, so I have to bring this to a close.